When it comes to versatility in score and sound, Emmy nominated composer Nathan Barr is at the leading-edge of today’s sonic landscape. “I always think, ‘How can I push a sound into a place where no one’s heard it before?’” says Barr of his work on Amazon’s Carnival Row. The composer is up for three Emmy awards at this year’s virtual ceremony, bringing his grand total to five career nominations.

Barr’s impressive resume includes scoring seven seasons of HBO’s True Blood as well as FX’s The Americans and Netflix’s Hemlock Grove, the latter two earning him double Emmy nomination in 2013 for Main Titles.

This year, Barr is up for Outstanding Main Title Theme for Carnival Row and Hollywood as well as an Outstanding Music Composition for his Hollywood score. The two shows are vastly different from one another, and the music mirrors that diversity.

Hollywood’s focus on the film industry in the 1940s called for a period score, allowing Barr to lean into the swinging and jazzy flavors of the time. “There’s a very detailed way the music interacts with the picture that’s very specific to the 40s,” Barr explains.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Carnival Row, a neo-noir fantasy series featuring fairies and all sort of mythical creatures. Utilizing instruments that Barr invented, he built an expansive sound pallet for the series. The eerie and ethereal presence he created perfectly accompanies the visual textures of the show’s cinematography.

Awards Focus spoke with Barr about his trio of Emmy nominations, how he channeled old Hollywood glamor for Ryan Murphy, and why he invented instruments for Carnival Row.

Awards Focus: How did you first get involved with Hollywood? Can you tell me about the first conversations you had with Ryan Murphy?

Nathan Barr: Alexis Woodall, Ryan Murphy’s right hand and head of his company, got in touch with me about a year ago. She wanted to bring me into the Ryan Murphy camp to start working on some shows, and the first one would be Hollywood. I’ve never even met Ryan, but Alexis is incredibly involved. She works with the composer to get the music to a place where she feels it’s really working, and then Ryan sees it and makes notes. She’s very hands-on and very knowledgeable when working with a composer.

AF: What kind of guidance and initial instruction did she give you?

Barr: She told me that the music should lean into the period. Sometimes with period pieces, they want to go contemporary with the music. That was not the case here. They really wanted to lean into the orchestration and melodic styles of that of that time period.

AF: Hollywood plays into this feeling of old Hollywood glamour and nostalgia, but it also delves into the darkness of all of that. How did that influence the score?

Barr: You can see it particularly with Jack’s melody, which is the melody you hear throughout most of the main title. It has an enthusiasm and an innocence, but also a fragility. That was meant to plug into the idea of the starry-eyed actors that come to Hollywood each year by the thousands, even to this day. It’s always such a precarious journey, and people are asked to do things that they never expected. Jack is certainly one of those people, so I wanted to plug into the deviousness of those moments when needed. The music really played to the tragedy of what was happening on screen.

AF: With Hollywood being a period piece, are there any movies or scores from that time period that you were particularly inspired by or you wanted to emulate?

Barr: When I think of the great composers of that time period, I think of Franz Waxman, Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, Alex North. I love a lot of films from the 30s and 40s – one of the major ones being Captains Courageous, which was scored by Franz Waxman. I leaned into some of his orchestrations and his ideas about melody to plug into Hollywood.

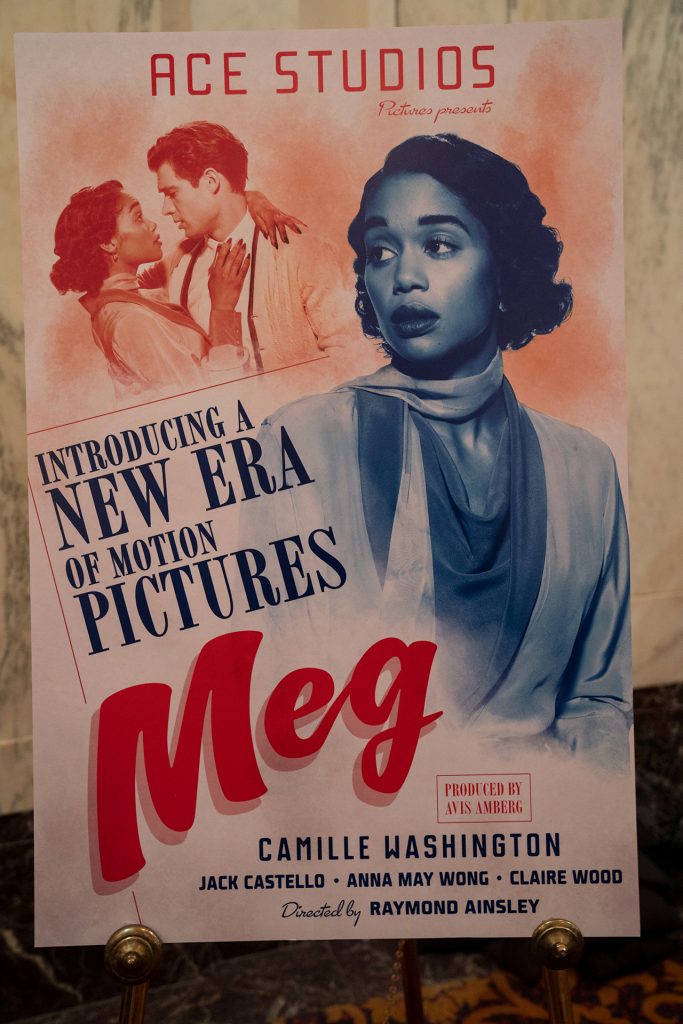

AF: Within Hollywood, there’s the movie Meg, and that has its own score. How did you approach that?

Barr: I felt like a kid in a candy store. How often do we, as composers today, get to really lean into a period film and then reimagine and score that? I plugged into an orchestration style and a melodic style that’s slightly melodramatic, because that’s how it was in those times.

When we hear those scores today, they smack of melodrama, but for that time period, it works beautifully. There’s a very detailed way the music interacts with the picture that’s very specific to the 40s. There’s a lot of solo violin in that Meg score, and it’s laying on thick with the sliding and the vibrato. It seems to work very well.

AF: Hollywood tackles a lot of pretty heavy social issues like racism and homophobia. When you’re scoring scenes of that nature, what’s your first instinct?

Barr: I focus on the human story and the emotional component of those things. As long as I was able to plug into the emotional core of the character in a moment, then I felt it was successful. That’s the most important thing. The show takes care of those particular issues beautifully with the way it’s shot, acted, and written.

AF: Was there any one episode or scene that stood out as the most challenging or the most fulfilling?

Barr: The main title was one of the biggest challenges. It’s an incredible main title, with all the actors climbing up the Hollywood sign. The schedule was a bit crazy, and the picture changes were happening at a mile a minute. I had to chase the visuals and determine: how triumphant should it be? How upbeat, how driving? How emotional?

If you look at the laundry list of things that Alexis and I were going for at the start, I would have said it’s impossible to have a single piece of music do that in a minute. But we got there in the end. The visual storytelling, specifically that beautiful shot at the end, allowed us to plug into the emotional part of things.

AF: When you are working on the main title, how does that process differ from when you’re working on the score as a whole?

Barr: It’s similar to writing a short story version of a novel. Your ideas need to be stated really quickly, because you have so little time. It’s all about the economy of what you’re choosing, and maximizing the emotional impact. It’s oftentimes bigger, brasher or bolder than what you’re doing in the body of the show. Ultimately, you want the main title to immediately tell the audience what they’re going to be experiencing.

AF: Let’s switch gears and talk about Carnival Row. How did you channel that otherworldly feeling when working on the main title?

Barr: As a composer, I have a huge collection of musical instruments, including this massive pipe organ. Just as there are all sorts of fantastical beasts and creatures in the show, I have a musical version of that in my studio.

It was about leaning into sounds that the audience wouldn’t be familiar with to help sell the otherworldliness of the visuals. It was so important to get the thematic component in there. There’s the theme of the row, and a taste of Philo’s theme at the end. That’s played on these tuned sleigh bells, which are a part of the organ. It wanted to be big and sweeping and dramatic and otherworldly and fantastical.

AF: You used some unusual instruments, and invented a cello for Carnival Row. Can you tell me about that?

Barr: The cello has five main strings instead of four strings. It has ten sympathetic strings, which you see in Indian instruments, and it has a mechanical drone with four strings on it. You hear it particularly with Philo – the first time you hear his theme is on solo cello. Another instrument you hear throughout the show is a pipe organ-based instrument that allows me to experiment with the pipes. That’s a signature sound for the show.

AF: How did that come about, and what made you decide to use those instruments?

Barr: I’m always thinking about how to take something that’s familiar like a cello and make it unusual. In this case, I wanted a cello that was self-accompanying. I was recording the drone, and then playing over the recording, and I thought: Why can’t I just do this live? Why can’t I just have a drone and play over it?

I wondered if there was a way to create a mechanical drone on the cello itself. I brought that idea up to a luthier in Santa Cruz, and they spent four years building it. I always think: how can I push a sound into a place where no one’s heard it before? That becomes a part of my unique sound.